For over 70 years, The New Musical Express (better known as the NME) has been an iconic voice in the music industry, shaping the conversation around rock, pop, and indie music. Founded in 1952, the NME quickly became a staple for music fans, offering up insightful reviews, exclusive interviews, and the latest news on the hottest acts.

From its early days covering the rise of rock and roll to its more recent focus on indie music, the NME has remained at the forefront of music journalism, influencing generations of music fans and shaping the direction of the industry.

In this article, we’ll explore the fascinating history of The New Musical Express from its origins to its current legacy.

1950s.

The paper’s first issue was published on the 7 March 1952 after the Musical Express was bought by London music promoter Maurice Kinn and relaunched as the New Musical Express (commonly shortened to NME). It was initially published in a non-glossy, tabloid format on standard newsprint. On 14 November the same year, taking its cue from the US Billboard Magazine, it created the first UK Singles Chart. The first of these was, in contrast to more recent charts, a top twelve sourced by the magazine itself from sales in regional stores around the UK. The first number one was “Here In My Heart” by Al Martino.

1960s

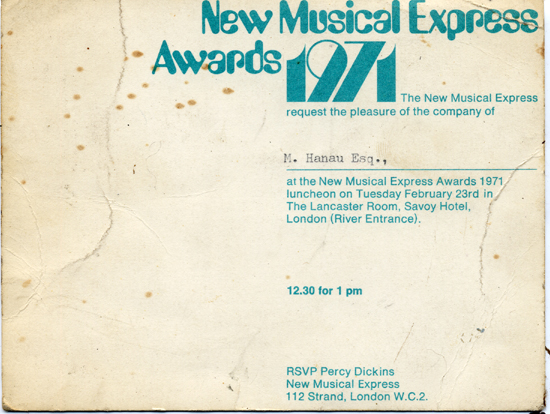

During the 1960s it championed the new British groups emerging at the time; The Beatles and The Rolling Stones were the two most notable groups to emerge during this era and they were frequently featured on the front cover. These and other artists also appeared at the NME Poll Winners Concert; an awards event that featured artists voted as most popular by the paper’s readers. The concert also featured an awards ceremony where the poll winners would collect their awards. The NME Poll Winners Concerts took place 1963-1966. They were filmed, edited and then transmitted on British television a few weeks after they had taken place.

The latter part of the 1960s saw the paper chart the rise of psychedelia and the continued dominance of British groups of the time. It was in the late 60s that pop music started to be called rock – and groups referred to be called bands. During this time (and for many years afterwards) the paper became engaged in a sometimes tense rivalry with its fellow weekly music papers Melody Maker, Disc, Record Mirror and Sounds. NME sales were healthy with the paper selling as many as 200,000 issues per week, however things were due to change.

1970s

By the early 1970s the NME had lost ground to the Melody Maker as its coverage of music had failed to keep pace with the development of rock music, following the advent of prog and psychedelia, which were both wildly popular at the time. In early 1972, with the paper on the verge of closure by its owners IPC (who had bought the paper from Kinn in 1963), Alan Smith was made editor and the paper’s coverage changed radically from an uncritical and rather reverential showbiz-oriented paper to something that was smarter, hipper, cynical and funnier than any mainstream British music paper had ever been (an approach influenced mainly by writers such as Tom Wolfe and Lester Bangs). In order to achieve this, Smith raided the underground press for its best writers, such as Charles Shaar Murray and Nick Kent, and recruited other writers such as Tony Tyler and Ian MacDonald.

By the time Smith handed the editor’s chair to Nick Logan (who would later launch Smash Hits and The Face) in mid-1973, the paper was selling nearly 300,000 per week and was outstripping its other weekly rivals. However the NME had begun to be seen as ‘out of touch’ and by 1976 something new was about to drastically change the music industry and, inevitably, NME.

1976 saw Punk arrive into what was seen as a stagnant music scene and NME fell behind its rivals in reporting and covering this new music. The NME would even be sneered at by The Sex Pistols in the lyrics of their song Anarchy In The UK. The NME was seen as The Enemy and very much part of the music establishment that Punk was rebelling against.

To help boost the paper the NME famously advertised for a pair of “hip young gunslingers” to join their editorial staff. This resulted in the recruitment of Tony Parsons and Julie Burchill. The pair shook the paper up and they became champions of the Punk scene and created a new tone for the paper. Bands who only a few months previously were criticising the paper were now eager to be included. Logan had turned the paper back into being a vibrant essential of youth culture again.

In 1978 Logan moved on, and his deputy Neil Spencer was made editor. One of his earliest tasks was to oversee a redesign of the paper by Barney Bubbles, which included the logo still used on the paper’s masthead today (this made its first appearance towards the end of 1978). Spencer’s time as editor also coincided with the emergence of post-punk acts such as Joy Division and Gang of Four. This development was reflected in the writing of Ian Penman and Paul Morley, whose intense postmodernist prose perhaps baffled as much as it informed and educated its readers. Danny Baker, who began as an NME writer around this time, had a more straightforward and populist style.

The paper also became more openly political during the time of Punk, often its cover would cover youth oriented issues rather than a musical act. The paper was part of the support against the rise in racist political parties like the National Front, the election of Margaret Thatcher in 1979 would see the paper take a firm socialist stance for much of the following decades.

1980’s

The NME’s direction started to get confused around the start of the decade, pop music at the start of the 1980s was diverging in different directions (e.g. the new pop of acts such as ABC and Haircut 100, and the New Romantic movement). Also, the line of criticism started to become more ideological – for instance, the term rockism is thought to have originated in the paper’s pages.

However it still covered new bands like The Specials and covered the riots which engulfed many British cities in 1981. It infamously had an issue devoted to the rising problem of youth suicide which is rumoured to be among one of the poorest selling issues in its history.

The NME responded to the Thatcher era by promoting socialism through the Red Wedge fronted by Billy Bragg. A week before the 1987 election the paper featured an interview with the leader of the Labour Party, Neil Kinnock and his photo on the cover. Writers at this time included Mat Snow, Barney Hoskyns, David Quantick and Neil Spencer.

In 1981 the NME released the influential C81 cassette tape in conjunction with Rough Trade Records, available to readers by sending in a coupon from the magazine. The tape featured a number of then ‘up and coming’ bands, such as Aztec Camera, Orange Juice, Linx, Scritti Politti as well as a number of loosely ‘post-punk’ artists such as Robert Wyatt, Pere Ubu, Buzzcocks and Ian Dury. A second, more influential tape (called C86) was released in 1986.

During this time the British music scene was growing increasingly stagnant again, some new C81 bands saw some limited success but it was The Smiths and the bands enigmatic lead singer Morrissey who would help focus the paper again. The NME would become a champion of the band and would have devoted Smiths fans inundate the papers letters page in praise of the band. This and the paper’s uncritical devotion to The Smiths and in particular Morrissey would lead the paper to be called “The New Morrissey Express” from some critics.

However sales were dropping, and by 1985 NME had hit a rough patch and was in danger of closing. During this period (now under the editorship of Ian Pye, who replaced Spencer in 1985), they were split between those who wanted to write about hip hop, a genre that was relatively new to the UK, and those who wanted to stick to rock music. Sales were apparently lower when photos of hip hop artists appeared on the front and this led to the paper suffering as the lack of direction became even more apparent to readers.

The NME was rudderless at this time with staff pulling simultaneously in a number of directions. It was haemorrhaging readers who, ironically, were deserting NME in favour of Nick Logan’s two creations The Face and Smash Hits. This was brought to a head when the paper was about to publish a poster of the cover of the Dead Kennedys’ album Frankenchrist. The cover was a painting by H.R. Giger called Penis Landscape, then a subject of an obscenity lawsuit in the US. Three senior editorial staff were sacked, including Pye, and Media Editor, Stuart Cosgrove. Alan Lewis, something of a magazine genius in the Nick Logan mould, was brought in to rescue the paper mirroring Alan Smith’s amazing revival a decade and a half before.

This proved to be a success and the paper brought in new writers such as Danny Kelly, Andrew Collins, Stuart Maconie and Steven Wells to turn the paper round and give it a sense of direction, although Mark Sinker left in 1988 after the paper refused to publish a negative review he wrote of U2’s Rattle and Hum. Initially many of the bands on the C86 tape were championed as well as the rise of Goth rock bands but new bands such as Happy Mondays and The Stone Roses were coming out of Manchester. Plus the paper eventually came round to the Acid House scene which with the Manchester scene (dubbed Madchester by the paper) helped give the paper a new lease of life again.

1990’s

The start of 1990 saw the paper in the thick of the Madchester scene, plus it was covering the new British indie bands, dubbed Shoegazers by the NME in the late 1980s.

By the end of 1990, the Madchester scene was dying off, acid house was suffering from being the subject of a vigorous campaign to outlaw it by the John Major government, and NME had started to report on new bands coming from the US, mainly from Seattle. These bands would form a new movement called Grunge and by far the most popular bands were Nirvana and Pearl Jam. The NME took to Grunge instantly and although it still supported new British bands, the paper was dominated by American bands, as was the music scene in general..

Although the period from 1991 to 1993 was dominated by American bands like Nirvana, this wasn’t to say that British bands were being ignored. The NME still covered the Indie scene and was involved with a war of words with a new band called Manic Street Preachers who were criticising the NME for what they saw as an elitist view of bands they would champion. This came to a head in 1991 when during an interview with Steve Lamacq, Richey Edwards would confirm the band’s position by carving “4real” into his arm with a razor blade..

By 1992, the Madchester scene had died and along with The Manics, some new British bands were beginning to appear. Suede were quickly hailed by the paper as an alternative to the heavy Grunge sound and hailed as the start of a new British music scene. Grunge however was still the dominant force, but the rise of new British bands would become something the paper would focus more and more upon.

1992 also saw the NME have a very public dispute with its former hero Morrissey due to allegations of him using racist lyrics and imagery. This erupted after a concert at Finsbury Park where Morrissey was seen to drape himself in a Union Jack. The article which followed in the next edition of NME[1]soured Morrissey’s relationship with the paper and this led to Morrissey not speaking to the paper again for over a decade. When Morrissey did eventually speak to the NME in 2003 he made it clear that he was content with speaking to the paper again as the three writers concerned had long since left..

In April 1994 Nirvana frontman Kurt Cobain was found dead, a story which affected not only his fans and readers of the NME, but would see a massive change in British music. Grunge was about to be replaced by Britpop, a new form of music influenced by British music of the 1960s and British culture. The phrase was coined by NME after the band Blur released their album Parklife in the same month of Cobain’s death. Britpop began to fill the musical and cultural void left after Cobain’s death, and Blur’s success, along with the rise of a new group from Manchester called Oasis saw Britpop explode for the rest of 1994. By the end of the year Blur and Oasis were the two biggest bands in the UK and sales of the NME were increasing thanks to the Britpop effect. 1995 saw the NME cover many of these new bands and saw many of these bands play the NME Stage at that years Glastonbury Festival where the paper had been sponsoring the second stage at the festival since 1993. This would be their last year sponsoring the stage, subsequently the stage would be known as the ‘Other Stage’..

August 1995 saw Blur and Oasis plan to release singles on the same day in a mass of media publicity. NME editor Steve Sutherland leapt on this and stuck the story on the front page of the paper. This saw Sutherland come in for criticism for playing up the duel between the bands. Blur won the ‘race’ for the top of the charts, and the resulting fallout from the publicity led to the paper peaking in sales during the 1990s as Britpop became the dominant musical genre. After this peak the paper saw a slow decline as Britpop burned itself fairly rapidly out over the next few years. This left the paper directionless again, and attempts to embrace the rise of DJ culture in the late 1990s only led to the paper being criticised for not supporting rock or indie music.

Sutherland did attempt to cover newer bands but one cover feature on Godspeed You Black Emperor! in 1999 saw the paper dip to a sales low, and Sutherland later stating in his weekly editorial that he regretted putting them on the cover. For many this was seen as an affront to the principles of the paper and sales reached a low point at the turn of the millennium.

2000s

In 2000 Sutherland left to become Brand Director of the NME, replaced as editor by 26 year-old Melody Maker writer Ben Knowles. The same year saw the closure of the Melody Maker (which merged with the NME) and many speculated the NME would be next as the weekly music magazine market was shrinking. The monthly magazine Select that had thrived especially during Britpop was closed down within a week of Melody Maker. “NME” reasserted its position as an influence in new music, helping to break bands including The Strokes and The White Stripes.

In 2002 Conor McNicholas was appointed as editor and with a new wave of photographers Dean Chalkley, Andrew Kendall, James Looker & Pieter M.Van Hattem and a high turnover of eager young writers the paper slowly began to increase in sales, plus it focused on new British bands such as the The Libertines, Kaiser Chiefs and Franz Ferdinand. The paper was now no longer printed on newsprint but had glossy full colour covers and had begun to develop into more of a magazine format.

NME’s Digital Transformation

In 2018, the NME made the decision to stop printing its weekly magazine and focus on its digital platform. The move was part of a broader shift in the music industry towards digital consumption, with more and more fans turning to streaming services to discover new music.

Final words

The New Musical Express (better known as the NME) has played a vital role in the music industry for over 70 years. From its early beginnings covering the rise of rock and roll to its current focus on indie music, the NME has remained at the forefront of music journalism, shaping the conversation around music and influencing generations of fans.

While the magazine may no longer be in print, the NME’s digital platform continues to be a source of insightful and entertaining music coverage, offering fans around the world access to the latest news, reviews, and interviews. As the music industry continues to evolve, the NME remains a vital part of the conversation, celebrating the legacy of an iconic musical institution.